3 pieces on the varying difficulties of leadership

Eric Jaffe laments the Obama administration's lack of progress with its "livability" initiative:

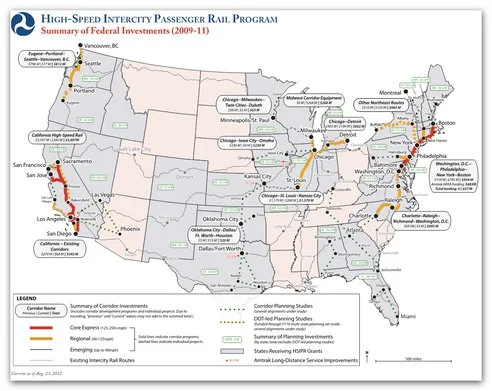

Fast forward five years since that 2009 pledge, and many of the most hopeful transformations have yet to arrive. A proposed national network of high-speed rail is little more than a wishful map. The Highway Trust Fund, which pays for road maintenance as well as transit programs, will run out of money any month. Streetcars with questionable mobility value represent perhaps the most visible addition to city transport systems. There have been some minor victories — transit use is up in places, and bike systems are robust in others — but many more defeats.

...

Fein seems unsure where to issue this reckoning. Was the livability program "undermined" by entrenched highway interests? Or were federal officials not serious enough about their intentions? He does lay much of the blame on the term livability itself; imprecise for policy purposes, it meant different things to different people, and in that way often meant nothing at all.

Big ships take a long time to turn, and the federal government is the biggest of ships. Policies and plans are very difficult to change when entrenched interests don't want them to change and when there's no effective political push for an alternative (i.e., lobbyists with money). Until there's a big lobby with lots of people and/or money, expect very slow change. The good news in my mind is that cities don't need to wait around for the feds - nearly all of their destiny is in their own hands. The bad news: in the current political environment, you can forget about any large new initiative, including high-speed rail.

Next up: Rob Steuteville implores leaders of bike-ped movements and urbanists to get together:

Yet this report also reveals a big hole in this movement — many ped-bike advocates rarely talk to urbanists and vice-versa. The report has about 40 authors and reviewers – representing major nonprofit, academic, and government institutions. They appear to be only vaguely aware of a key factor in the success of nonautomotive transportation: Place-based planning and development.

...

The main difference between Boston and Jacksonville is not sidewalks, trails, “complete streets” policies (neither city has one), or crosswalks — all of which are emphasized in the report and all are important in their way. Yet you can place a sidewalk, crosswalks, and bike lane on an eight-lane urban arterial lined with parking lots and big box stores and few people will get out of their cars — mostly those who have no choice. The real difference is the way these two cities are organized. Boston is built to be walkable and bikable, and Jacksonville is not.

In my humble opinion (don't we always say that when we aren't feeling humble?): the onus is on urbanists. We need to do a much, much better job communicating the impact urban design has on people's day to day lives. Advocates of biking and walking are generally laypeople with a passion for it for some very personal reason, often health. We can't expect even bike-walk advocates to know as much about design as professionals immersed in the field.

It reminds me of many conversations I've had with fellow architects over the years, who lament the general public's lack of understanding of architecture. I would generally ask, "what have you done to change that? Who have you talked with? What group have you spoken to in order to spread the word?" And, it's one reason I wrote this book, whose intention is to speak more directly to non-professionals. The locavore movement has had results by reaching out to people of all stripes, using all media available. We can learn a few things.

Finally... Scott Wiener writes about friction between the needs of walkability and the fire department:

In San Francisco, we’ve experienced first-hand the challenges created by having wide streets and the benefits of moving toward narrower, more walkable streets. We’re also experiencing a bureaucratic backlash against our city’s efforts to avoid wide streets and to implement good urban design. This conflict is not unique to San Francisco, and to ensure a future of livable, safe streets, it’s imperative that policymakers everywhere push back against opposition to good street design.

...

Wider roads are less safe for all road users and particularly for pedestrians. The wider a road is, the faster the traffic. The faster the traffic, the more accidents will occur and the more severe those accidents will be. Wider roads create longer crossing distances for pedestrians, the impacts of which are felt particularly by seniors and people with small children or mobility challenges.

I've worked with fire departments that were very open and cooperative, and others that were intransigent. In my experience, it all comes from the attitude at the top. If the Chief or Marshall is open-minded, we can find very agreeable solutions. If they stick by the worst of the worst code books, it's nearly impossible. Leadership, as always, is the key.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site